Racial segregation was incredibly prevalent in the 20th century before and during the civil rights movement of the 1960s; however, this doesn’t mean racial segregation practices are completely eradicated in our society today. Segregational methods based on race and ethnicity are still established in a variety of societal sectors, one of which being the housing industry.

“Redlining” was a practice stemming from segregation, used by housing industry officials to categorically deny access to mortgages, insurance loans and other financial services to certain individuals or neighborhoods based on race or ethnicity. Despite the lack of widespread discussion regarding this issue, redlining continues to be a problem even and sometimes especially right in our backyard in the state of Minnesota.

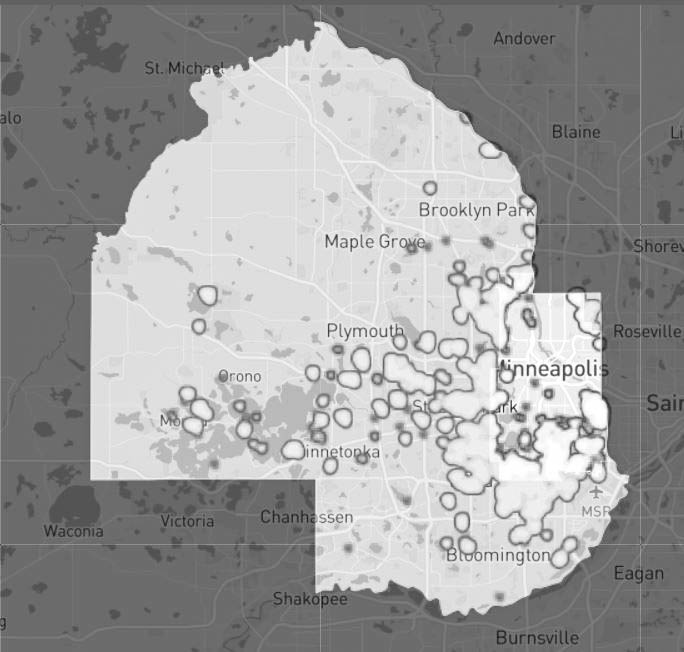

The Mapping Prejudice Project, based in the University of Minnesota Libraries, is working to identify and correctly map racial housing agreements that once prevented non-white families and individuals from buying and occupying homes in certain areas in Minnesota. The Mapping Prejudice Project team actively works with community members to “expose the history of structural racism and support the work of reparations.”

According to the Mapping Prejudice Project website, “the Twin Cities has the highest gap between black and white homeownership rates for any major metropolitan area in the country. While 78 percent of White families own homes in the Twin Cities, only 25 percent of Black families are homeowners.” These disparities are argued to stem from the redlining practices of the early 1900s, showing the long road ahead to bridge this gap.

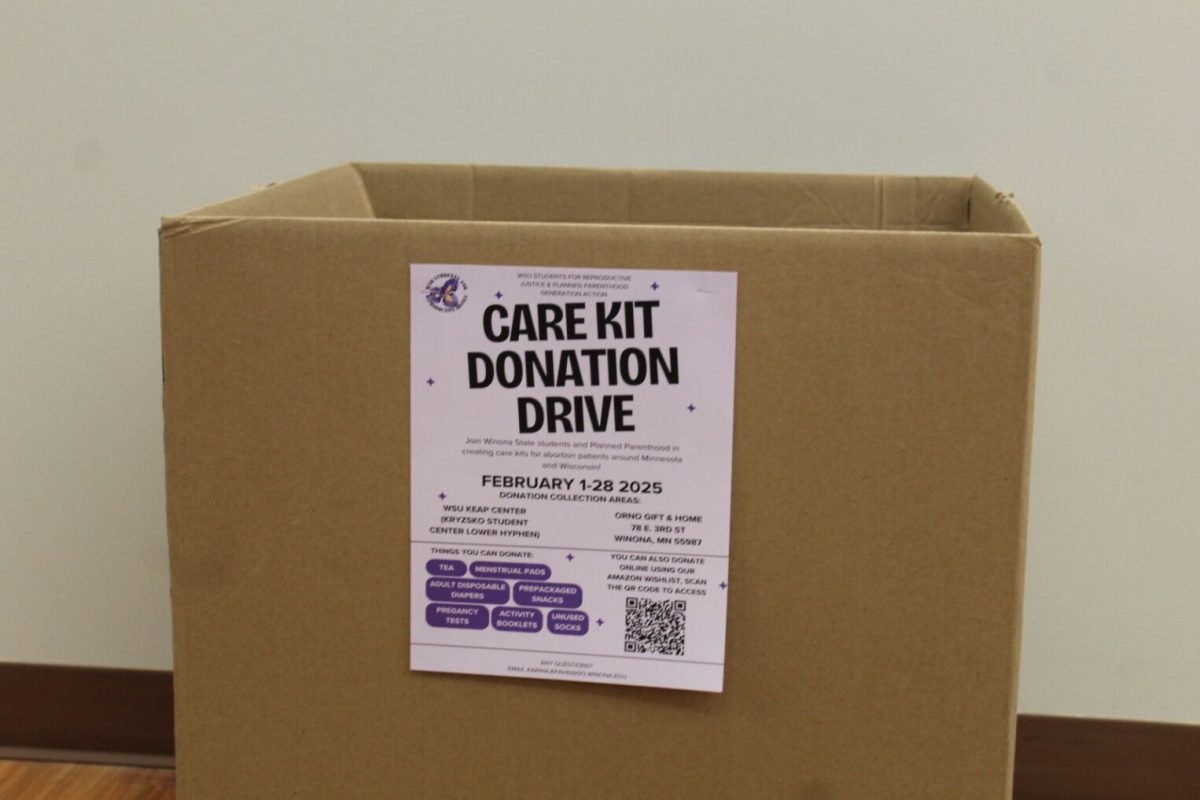

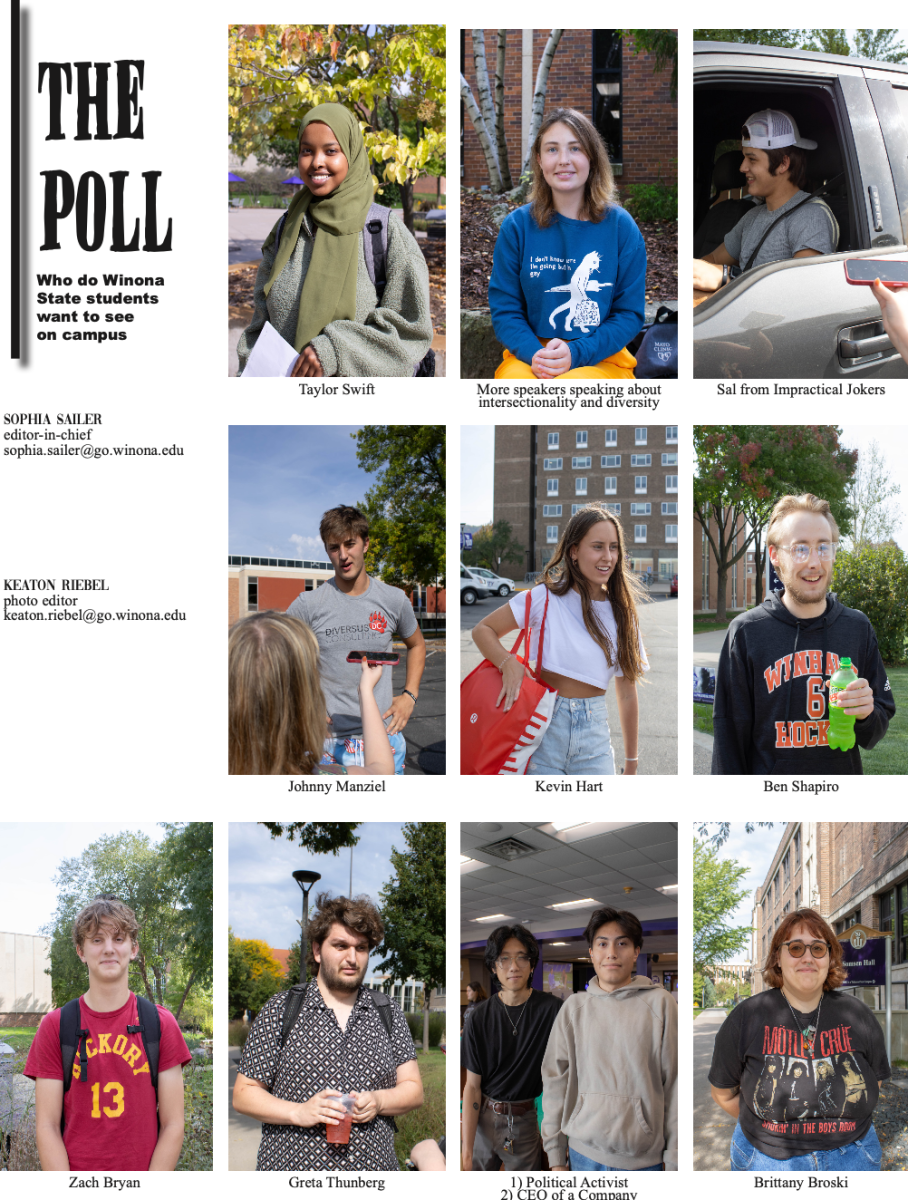

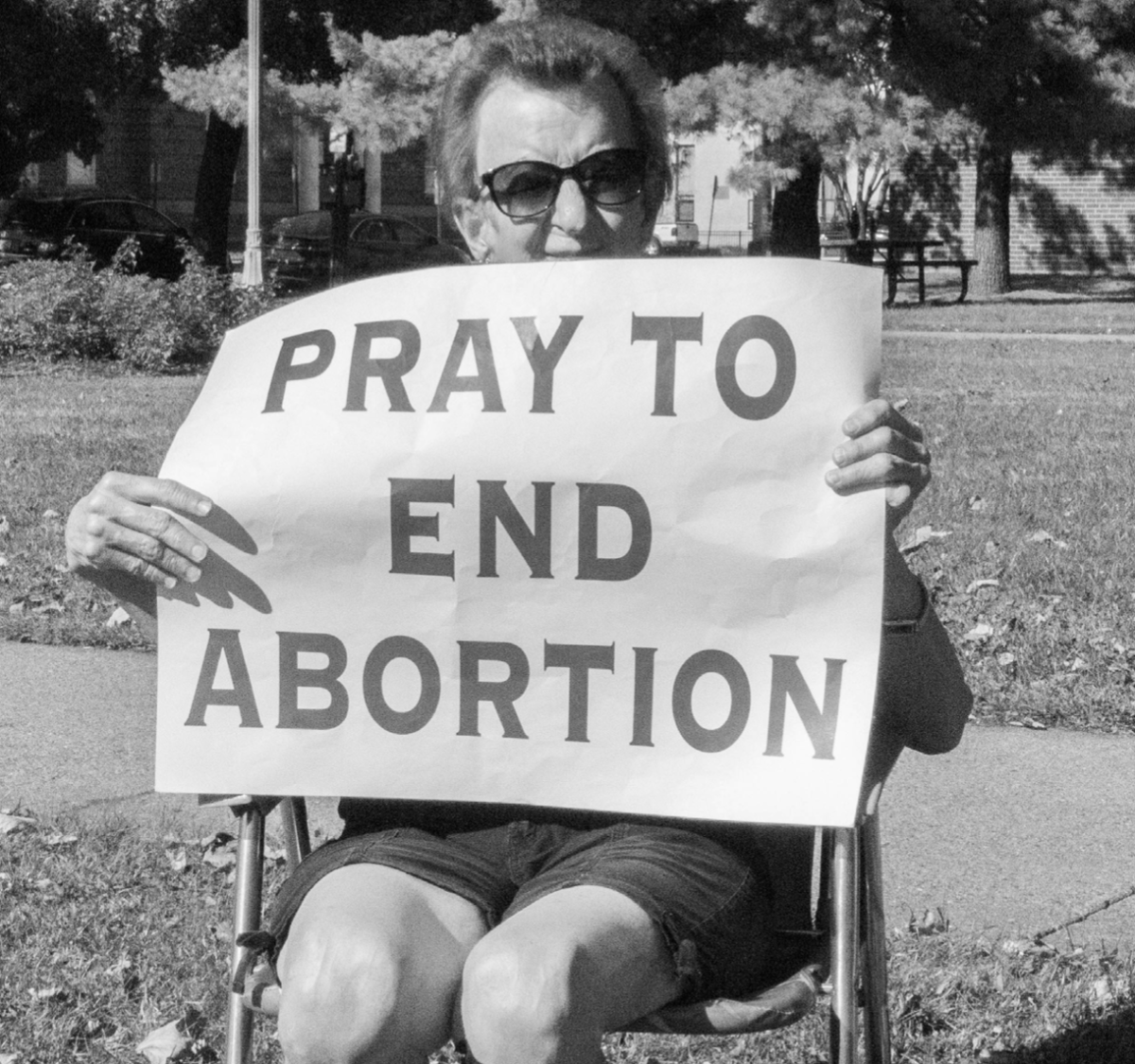

Jess Weis, a public relations major, women’s, gender and sexualities minor and co-president of Students for Reproductive Justice at Winona State, commented on the fact that Minnesota is a prevalent participant in the practice of redlining in the housing industry.

“Redlining was created [with the] intention to uplift white middle class families; as a result, it promotes a white supremacist ideal and removes any person of color- particularly black folks from benefiting from home ownership,” Weis stated. “it’s important to point out that this [is] still heavily prevalent in our own communities–and in our own state.”

According to the Metropolitan Council for the Twin Cities region, although Minneapolis-Saint Paul was ranked number one for home ownership rate in 2017, they were also ranked number one for their homeownership disparities between white residents and residents of color in the same year.

Racial covenants of the 20th century promoted segregation in Northern States that were more under-the-radar than the explicit racial segregation of Jim Crow laws. This historical foundation of homeownership disparities is still impacting the housing industry today, which is what the Mapping Prejudice Project is conducting more research on.

“This history has been willfully forgotten,” the Mapping Prejudice team states on their website. “So we created Mapping Prejudice to shed new light on these historic practices; we cannot address the inequities of the present without an understanding of the past.”

In the early 1900s, racial covenants found in early Minneapolis property records explicitly stated that homes could not be leased or mortgaged by anyone other than the “caucasian race” due to the belief that owners of other races and ethnicities would decrease the property values. Although racial covenants were declared illegal more than 50 years ago, Mapping Prejudice argues that these segregational policies have not completely vanished but are instead more implicitly ingrained into housing industry practices.

“Racial restrictions laid a foundation for contemporary racial injustices and continue to shape the health and welfare of the people who inhabit the landscape they created,” Mapping Prejudice states.

Like with any and all outdated and discriminatory practices, Weis states that voting appropriately to incite change is incredibly important.

“Lot of these public officials will shift the blame but very few will actually work to undo this racist reality, which is why we have to participate in local elections to ensure our communities receive the care and support they/we deserve,” Weis stated.