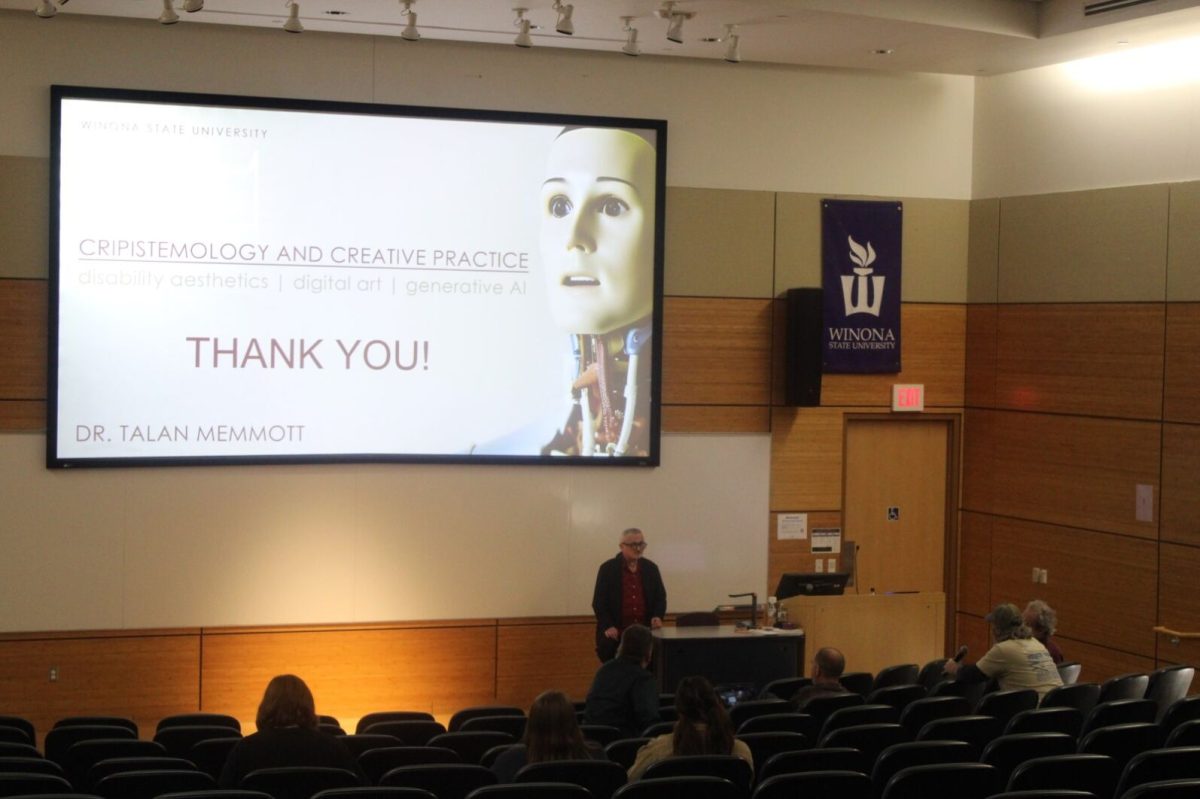

From uncanny self-portraits to monstrous medical amalgamations, Dr Talan Memmott’s perplexing presentation featured many works that reflect on what it is like to face a Laryngeal cancer diagnosis and help process the experience through reinvention of the self in digital art.

On February 26, in SLC 120, Dr Talan Memmott, artist, professor, and founder of the creative digital media program at Winona State, shared the process and purpose behind his works. This talk is the newest installment to the Consortium for Liberal Arts & Sciences Promotion (CLASP) series.

His presentation didn’t begin like most. Rather than opening with a detailed prologue, he opened a video titled “Introducing Lary”. It told the story of a chapel in San Biagio, adorned with many frescoes depicting Lary, the guardian of “neck-breathers.”

“Lary exists not as a mystical creature, half bird half man, as the video claims. But as a condition and medical reality. Lary with its one, rather than two R’s, along with the term ‘neck-breather’ are both nicknames for laryngectomies.”

The “historical shallow fake” of this pseudo-saint was revealed to be entirely fabricated by AI. Everything from the images, storyline, music, location, and even the narrator’s voice was generated across multiple platforms. Interestingly, the narrator’s voice was a clone of Dr Talan Memmott’s voice from a 2008 Electronic Literature in Europe seminar.

Grace Robins, an art education major, and Grace Seidel, a studio art major, shared their thoughts on the vocal clone.

“I like how he recreated his voice. That was really cool! I can definitely see how that could grow into an accessibility tool to help a lot of people.” Robins said. “When he was talking, I could definitely hear the correlation between the two voices.” Seidel agreed.

Initially, the audio narrator delivered the presentation until he handed the reigns off to the present Dr Memmott. The quality of his voice was noticeably different than the AI clone. After undergoing a larygectomy, a surgery that requires removing part of the voicebox, inflection and vocal control become much harder or non-existent.

“It’s like a medically enforced ventriloquism. The way I think of my voice, I think of it as some kind of ventriloquism,” Memmott said. “I don’t have a larynx. The TEP (tracheoesophageal voice prosthesis) is what’s causing my voice, so when I speak, it doesn’t feel physically like the way it would for others.”

He recounted a speech called Who’s the Dummy? and displayed another work that complimented the idea of “medically induced ventriloquism.” In a tryptic, two subjects, a medical dummy and Dr Memmott, became one in an uncanny collage of flesh and plastic.

“When he was talking, I could definitely hear the correlation between the two voices.” Seidel agreed.

Although AI creations can be associated with requiring little effort, creating these works is not as simple as typing in a prompt and selecting the first product. The AI often needs to be trained and conditioned, as it lacks an understanding of what certain medical interventions should look like. Dr Memmott uses various methods to achieve his desired outcome.

“I started using medical reports and journal entries as prompts. . . it could be that the medical jargon was just too much. After generating multiple AI images and using prompts to nudge the aesthetics in one direction or another, nine images were selected to be printed onto canvas.”

Robins and Caitlin Larsen, an art education and studio art major, both found the presentation fascinating.

“What stood out to me was the capability of AI and how it’s progressed. It’s crazy to think about what it could do in 2021 vs now. It has just grown really fast.” Robins said.

Larsen remembered a unit on AI, which gave her valuable background on the presentation.

“It was really fascinating to see the connections between what we saw here tonight and what we figured out during that class.” Larsen said.

The presentation concluded with a Q & A session. Many hands shot up with eager queries, a sure sign of an interested and engaged audience.