By Calline Cronin

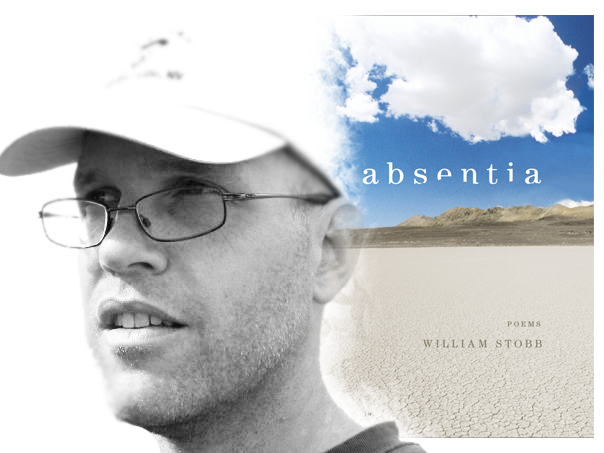

Winona State University’s Great River Reading Series hosted American poet William Stobb, who comically thanked the audience for attending his public reading instead of watching the Twins game on TV Wednesday night.

Stobb is originally from Little Falls, Minn., a small city that borders the Mississippi River, like Winona. He earned both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree at the University of North Dakota, where he discovered his passion for poetry.

Stobb taught English for 10 years at Viterbo University in La Crosse, Wis., where he still resides with his family. During Stobb’s writing career, his poems have been published in the American Poetry Review, the Colorado Review, the American Literary Review, the North Dakota Quarterly and the Denver Quarterly.

Earlier on Wednesday, Stobb visited Dr. James Armstrong’s advanced poetry class to participate in a question and answer session. The opening question, which prompted Stobb to explain his favorite part of poetry, segued into a discussion of Stobb’s life, and how he became inspired by modern poets from the Midwest.

“I think that my favorite thing about it [poetry] is that it’s versatility in a form,” he said.

Stobb sees poetry writing as a mode of communication, in which you can tell stories and explore territories where language is put under artistic pressure. He is particularly interested in juxtapositions of words—taking language out of the web of meaning and isolating certain aspects of it.

When asked how he turns off the critical mind that often plagues all writers, Stobb jokingly responded, “I have a switch.” But in reality, Stobb says there is a beginning period of about 10 minutes when he is fighting with himself. After the initial internal battle, Stobb shifts into the right state of mind to write.

“I get in a dynamic relationship, controlling what’s on the page and being responsive to what language happens inside,” he said.

Stobb’s love for writing poetry developed back in his college years, when he was introduced to poetry as a contemporary art form.

“I wasn’t a poetry reader,” Stobb admitted. “I had no idea that anybody wrote about stuff that happened here [in the Midwest].”

Specifically, Stobb was struck by one of Bill Holm’s poems, which described a pig falling off the back of a truck, because it was relatable and real.

“This could have happened on the county road outside my mom and dad’s house,” he said. “I was immediately called to write back to these poems.”

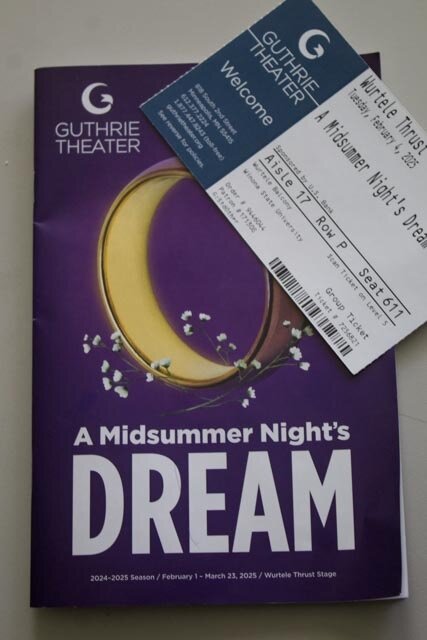

In 2007, Stobb’s first book of poetry, “Nervous Systems,” was published, followed four years later by “Absentia,” his most recent work.

Compared to “Nervous Systems,” Stobb says “Absentia” came together much quicker, but remains more emotional. Several of Stobb’s most personal poems in “Absentia” reflect his experience of living in the absence of people, those who had passed away.

“It’s a confusing book for me,” Stobb said. “Things happened that I wanted to communicate clearly. I wanted to sit down and write that out.”

Although Stobb has become quite the successful poet, he has had his fair share of rejections.

“It can be easy to get discouraged,” he admitted.

Yet Stobb advised Armstrong’s class of blossoming poets to accumulate rejection slips.

“Keep learning and keep getting better.”