Jordan Gerard/ Winonan

An “intervention of fate” made Civil Rights Freedom Rider Dave Dennis join the Civil Rights Movement, Dennis said in a speech to students, faculty and community members on Tuesday evening, Jan. 20.

Dennis was born to a sharecropper family in Louisiana and picked cotton with his family for nine years on a plantation until he moved in with an aunt. He was first in his family to graduate high school and “had no intention” of joining the Civil Rights Movement.

“I was scared to death,” Dennis said. “It was about survival. We were told to be respectful to white people.”

Dennis had plans to become an electrical engineer but “fate intervened” when he heard a lady speak about civil rights in 1961. She talked him into attending a Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) meeting and from there he attended a sit-in.

At the sit-in, police began arresting people for trespassing, including Dennis. He spent a week in jail, where he heard others talk about plans for the movement.

When he was released from jail, Greyhound buses full of people from Washington, D.C. and other northern cities rode through the south toward New Orleans, La., where a civil rights rally was planned.

These would later become known as the Freedom Rides of 1961, an effort to challenge segregated buses.

Many of the buses were bombed and destroyed by Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members and others against integration. Dennis participated in the first bus ride from Montgomery, Ala. to Jackson, Miss.

Dennis said the pivotal moment for him was at a meeting between the national leaders of the Civil Rights Movement and the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). The national leaders wanted the riots to stop, but SNCC wanted them to keep going.

“I was conflicted because I wanted to go back to school, but I also didn’t know if I should be there,” Dennis said. “And then what changed my life, fate would have, somebody said, ‘There’s not enough space in this room for both fear and God.’ I had to make a choice. And I chose God.”

Dropping out of college, Dennis was in the movement for good.

He went onto work for voter registration and improvement of education for African Americans. He also served as the co-director for Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) in Mississippi.

Dennis was close to many major Civil Rights Movement events and worked with other leaders from the movement, such as SNCC leader Bob Moses.

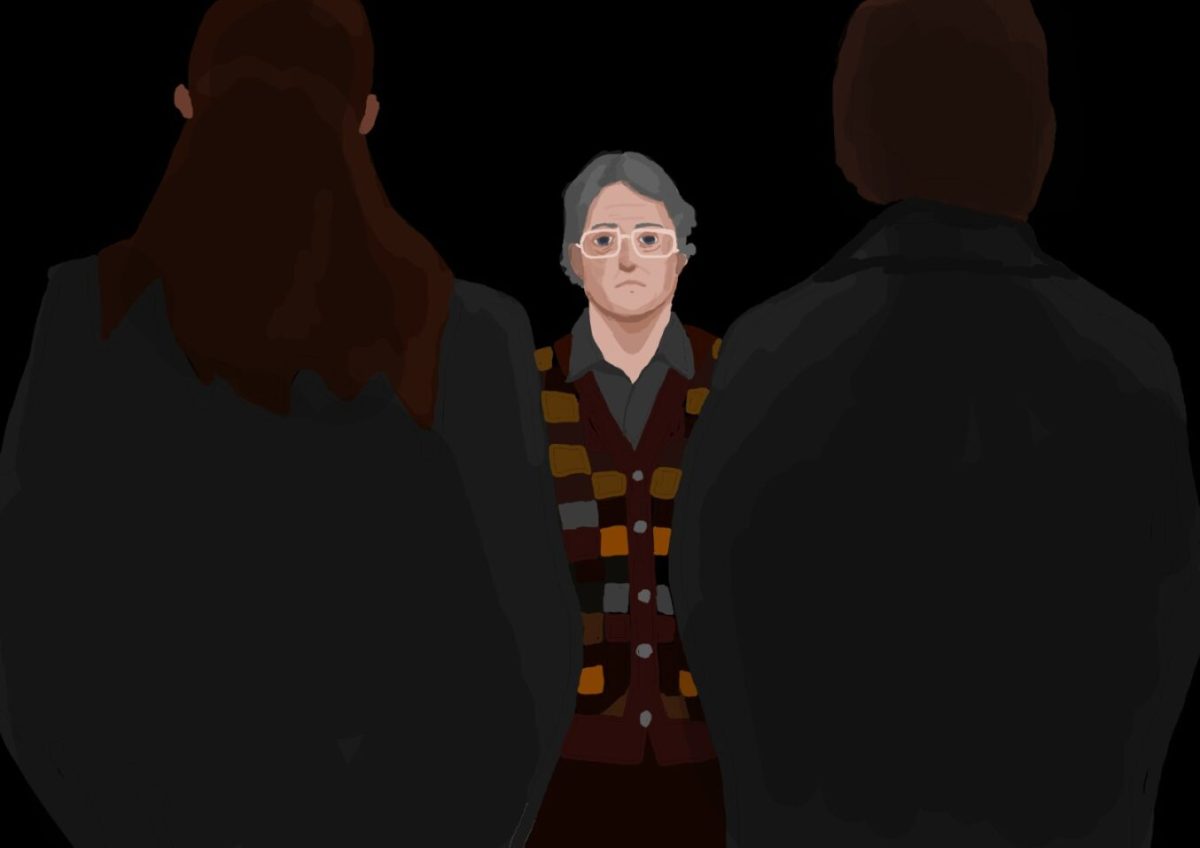

African Americans were prevented from registering to vote by white supremacists who controlled voter registration. If African Americans tried to register to vote, they were sometimes hurt, beaten or lynched, Dennis said.

Dennis was with Medgar Evers one hour before the KKK killed him. Evers asked him to come over to his house and watch a program with him, but Dennis declined and they parted ways, he said.

Later that night on July 12, 1963, hours after President John Kennedy’s public support of civil rights, Myrlie Evers called Dennis to tell him that her husband, Medgar, had been shot outside of their home.

Dennis also said that he was supposed to be in the car with Mickey Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney, three civil rights workers.

“I had to tell Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney to go to Meridian and do this organized work after a church burning,” Dennis said. “I was supposed to go with them, but due to a bronchial infection, I stayed behind. I got the call that they never checked in, and I just knew they were dead. I have never forgiven myself for that night.”

In 1964, Dennis was 23-years old-and had “experienced life and death at a young age.”

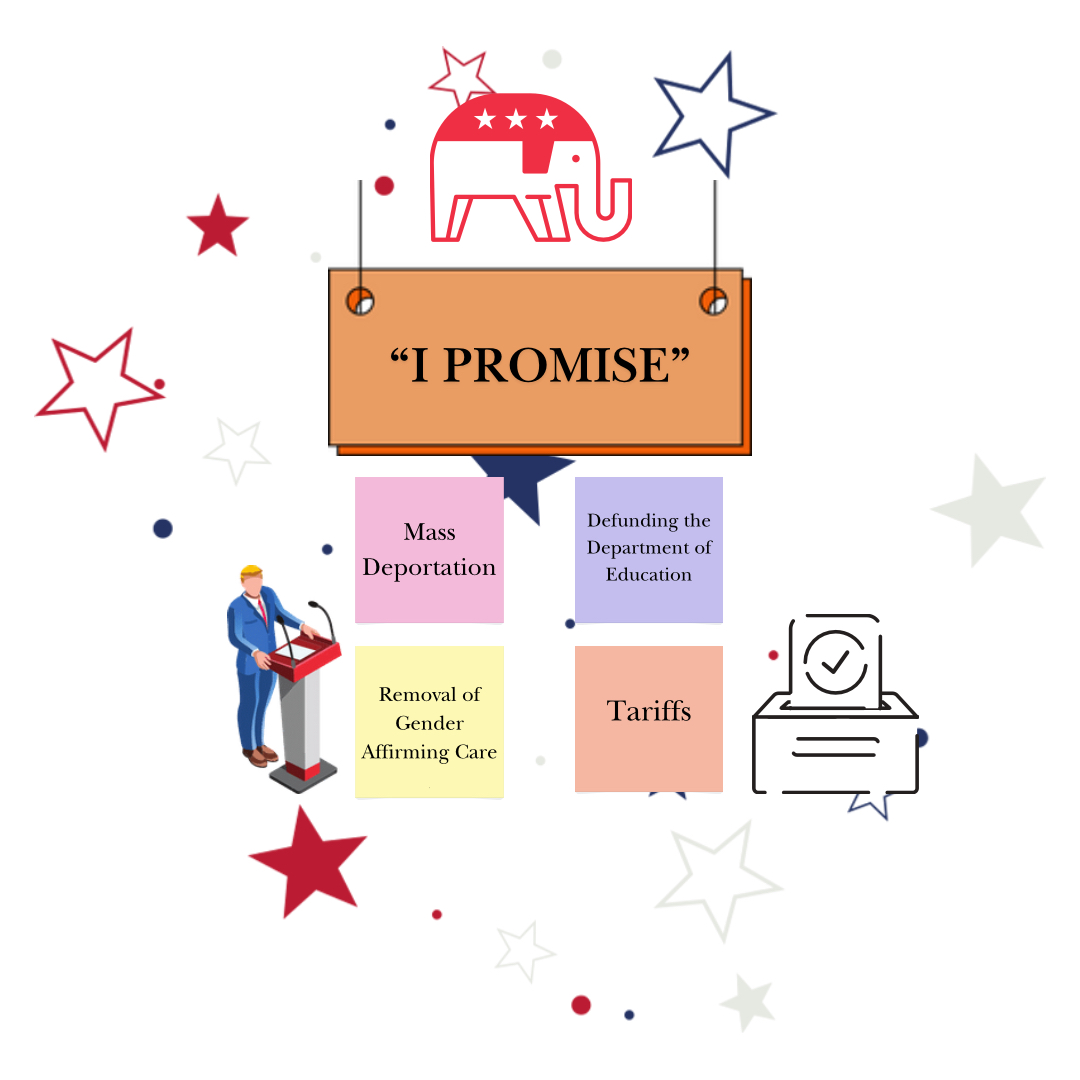

Dennis wrapped up his speech by asking the audience, “What type of America do we want to have if we want to live here?”

He added Mississippi had the most elected African-American officials in 1965 and since then, Mississippi is “at the bottom” for education, health care and economic development.

“What happened was blacks went into the white communities to integrate, but whites did not come into the black community to support those businesses,” Dennis said. “How did they survive? The family structure of black communities.”

He said he never knew his father, but he had other fathers in the extended family structures of his town.

“It takes a village to raise a community,” Dennis said. “Our families were broken up from day one when they brought slaves over, so they created this single-family structure. But what’s happening in this country is that we don’t have those communities anymore.”

He also said that education in New Orleans is now privatized after Hurricane Katrina and “students are not prepared for college.”

“Are we going to let this happen to us as a country?” Dennis asked the audience. “It’s no longer about black and white, but some people want us to think it’s about black and white, so we can fight against each other. We need to make the country a place you want for your children. It’s all up to you to make those changes, and the time is now because they aren’t waiting.”

After a standing ovation from the audience, Dennis answered questions from audience members.

Community member Jacob Grippen asked how we could improve the voter turn out in Winona County. Grippen is the vice chair of the Winona Human Rights Commission. He said this year’s turn out was 39 percent.

“People begin to lose faith that they have a voice,” Dennis responded. “You have to figure out how to make the change at home. You bounce the ball until someone comes and joins the game.”

The event concluded with Dennis encouraging audience members to “start the conversation and leave their footprint on this Earth doing something good.”