Jordan Gerard/Winonan

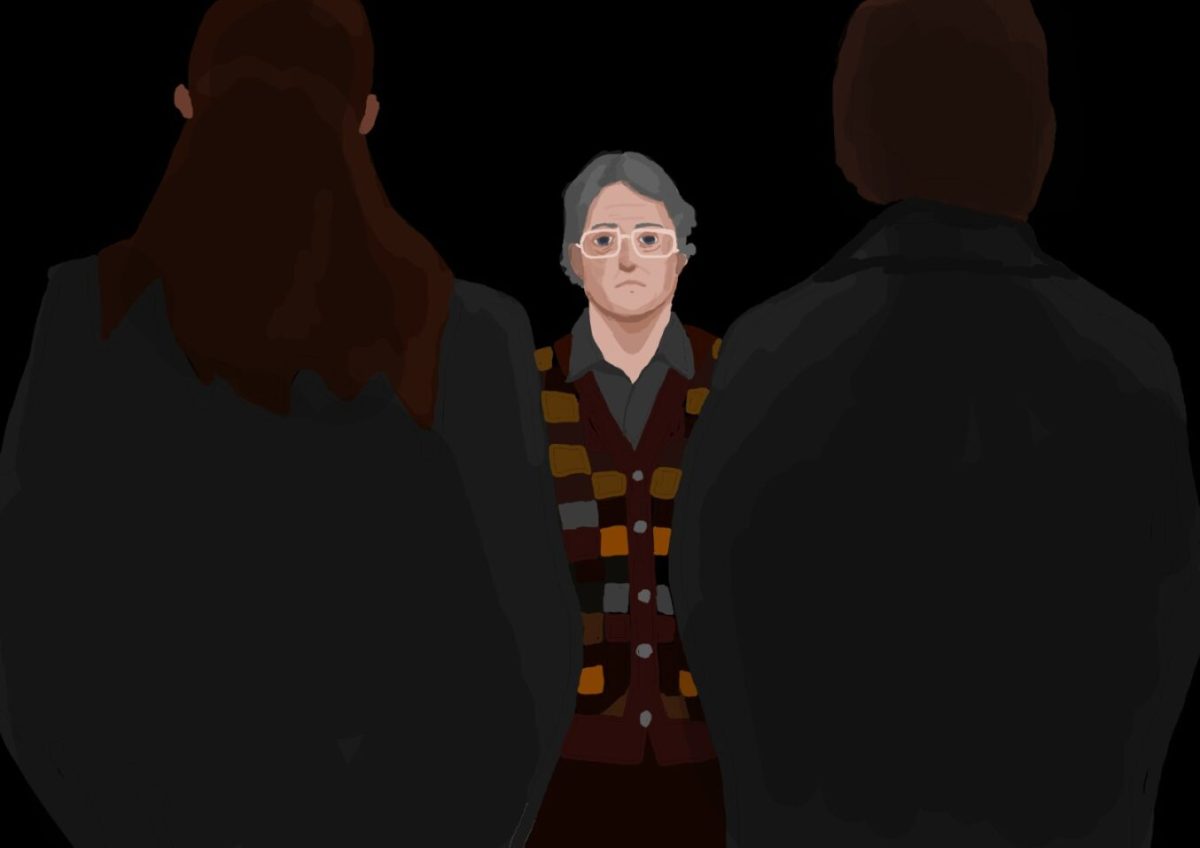

With an edgy humor about his past, Frank Meeink talked about his experience as a former skinhead turned activist to a full audience of students, faculty and community members on Tuesday, Sept. 22 in East Hall, Kryzsko Commons.

Meeink, 40, is a self-proclaimed “dirtball” kid from south Philadelphia, Penn. He said his childhood was very rough, with an abusive stepfather him and a drug-addicted mother.

“I didn’t want to go home after school, and this was how bad it got: every day when I walked home from school, I thought about this, ‘I should get hit by a car’,” Meeink said. “Because if I got hit with a car, I wouldn’t have to go home. I would go to a hospital.”

After his stepfather kicked him out at age 13, he went to live with his biological, drug addicted father in west Philadelphia. His new school was also a rough environment, but Meeink liked to participate in sports and was captain of the baseball team, which he said, “Some days it saved me, some days it didn’t.”

Meeink visited his aunt and uncle for a summer in Lancaster, Penn. He noticed his cousin, whom he looked up to, had changed his room from punk rock to swastikas and donned a Confederate flag and articles about skinheads and neo-Nazis on his walls.

“Every night, the skinheads would park their cars in the cornfields and come to my aunt and uncle’s house and climb up the balcony and sneak into my cousin’s room, and they’d always sit around and drink beer,” Meeink said. “They were always super cool to me.”

His cousin told the group Meeink lived in a rough neighborhood. Out of the group of guys, there was one girl, who could not believe Meeink’s life with different races.

“She couldn’t fathom that I rode the bus or train with black people every day,” Meeink said. “The skinheads would ask about my day or life; they showed me they ‘cared’ about me. It was someone saying, ‘How’s your life? How’s it going?’”

One night the group went to a concert and started beating up other white people with mullets. Meeink said he saw the fear in someone’s eyes and liked it.

“Deep down inside, I was a fearful child. I feared my parents, school, having enough food to eat, and now someone is afraid of me,” Meeink said. “Ego-maniac with no self-esteem–that’s what makes a gangster a gangster, a thug a thug, and a racist a racist.”

The skinheads shaved his hair off that night and accepted him into their group.

Meeink returned to Philadelphia and began recruiting kids into the movement. He also started to attend bible studies within the movement, where they told him to read the stories deeply and said, “God had chosen him to know the truth.”

Meeink said hate groups typically associated with religion.

At 15, he got a large swastika tattoo on his neck. He began to commit violent crimes regularly and was in and out of juvenile detention centers.

By 16, he had dropped out of school, and the movement put him in the underground due to his outstanding warrant.

He was living in a safe house with a few other guys in Indianapolis, Ind. when he got his first job working construction by using a fake alias.

One night while staying at his boss’s apartment, he was inebriated and contemplated suicide, but a neighbor saw him standing outside on the balcony with blood dripping from his wrists and called the police. The neighbor thought he had killed his boss, but when his suicide note was discovered, they transported him to a St. Catherine’s, a mental hospital.

When his friends had come to get him out, Meeink jumped through double-paned glass into the parking lot from the second story. Later, when writing his book, “Autobiography of a Recovering Skinhead,” the nurse at the hospital told him they changed a lot of policies at the hospital because of his escape.

He moved to Springfield, Ill. and started his own cable-access TV show about recruiting kids into the movement. The violent crimes continued, including a kidnapping. Meeink had taken someone hostage and videotaped himself beating the guy. He let his victim go, but the police later arrested him for aggravated kidnapping.

He was tried as an adult and sent to a county jail. While in county jail, he was put in the “hole” or solitary confinement. Meeink recalls he read a lot of books during this time and re-read the Bible.

“I read the bible every night until I fell asleep,” Meeink said. “I started fasting because if you fast, it’s said God will reveal himself to you.”

Meeink’s ultimate goal was to be freed from prison and to see the prison fall.

The prison offered him a compromise: if he would eat, they would place him in general population. He agreed.

“I knew there was a higher power,” Meeink said. “It gave me what I needed, not what I wanted.”

General population was diverse, Meeink said, so he did everything with the other inmates, even playing sports with them. His daughter was also born while he was in prison.

After he was released from prison, he talked to an African-American man on the way to meet his skinhead group. They start talking and joking. When he met up with the group, he realized he didn’t fit in with them anymore.

“I was talking to God. I understood that everyone’s equal,” Meeink said.

He got a job working for a Jewish man’s antique furniture business. The swastika tattoo was still on his neck and when he brought that up to his boss, the boss said, “I don’t care, just don’t break my furniture.”

When payday arrived, Meeink held onto his stereotypical monetary expectations of Jewish people. To his surprise he received the correct amount of wages, including an extra $100. Meeink continued to work for him.

Once Meeink broke a marble tabletop and apologized to his boss, along with saying, “I am so stupid. I am sorry.” His boss told him to stop saying he was stupid, and he was a thinker. The boss told him he could do whatever he wanted. On the way back Meeink was embarassed of his neo-Nazi appearance.

“I was grateful for this human being I had in my life every day,” Meeink said.

After his boss dropped him at his mom’s house, he took his neo-Nazi boots off and said he was done.

He admitted he was wrong. That was 19 years ago.

He said the movement jumped him at a funeral and threw him down a flight of steps. Meeink was completely done with the movement.

“I had a really bad credit score with my higher power in this world and I had to build it back up,” Meeink said.

In addition to his involvement with civil rights groups, he started a hockey program with the Philadelphia Flyers, called “Harmony Through Hockey” where they get more African-American and Latino kids to play the game to add diversity in the game. He even had his swastika tattoo removed for free by a Jewish professor.

Meeink emphasized the importance of empathy.

“If you have empathy for someone you cannot hate them. Or if someone has empathy for you, you later on cannot hate that person,” Meeink said.

Today he still maintains a relationship with the daughter he had while in prison. Once she was planning to visit her father for Christmas but warned him she had a boyfriend who identified as multi-racial.

“That’s fine by me,” he told her.

“I knew you wouldn’t care,” she said. “I just thought I’d tell you.”

Meeink said this meant the world to him, as it highlighted his growth from hatred to activism.