Kilat Fitzgerald / Winonan

Post-traumatic stress cuts deep into the fabric of the individuals impacted by it, and labeling such damage as a “disorder” can be detrimental in healing such scars.

This past Veterans Day, students at Winona State University were given a day off to reflect and think critically on what has been and continues to be sacrificed for the nation’s well-being. According to a Veterans Affairs study, over 20 veterans commit suicide each day, giving the warfighter challenges even after the initial battles on the frontline are fought.

Joshua Ploetz, a Winona State alumnus and former marine who served two tours in Afghanistan, is the U.S. Custodian of The Baton. The Baton is the handle of stretcher used by a Medical Emergency Response Team in Afghanistan, and now serves as a symbol of national conscience. It symbolizes pride, hope, courage and suffering.

“It’s neutral, nonpolitical, it has to cope with the reality of war, and it helps those who are in need regardless,” Ploetz said. “It is not any stretcher; it has been there for friend, enemy, and civilian.”

The marine has done much to raise awareness of the challenges of veterans. In 2014, he canoed the Mississippi river in order to “Paddle Off the War” while carrying the baton the whole way.

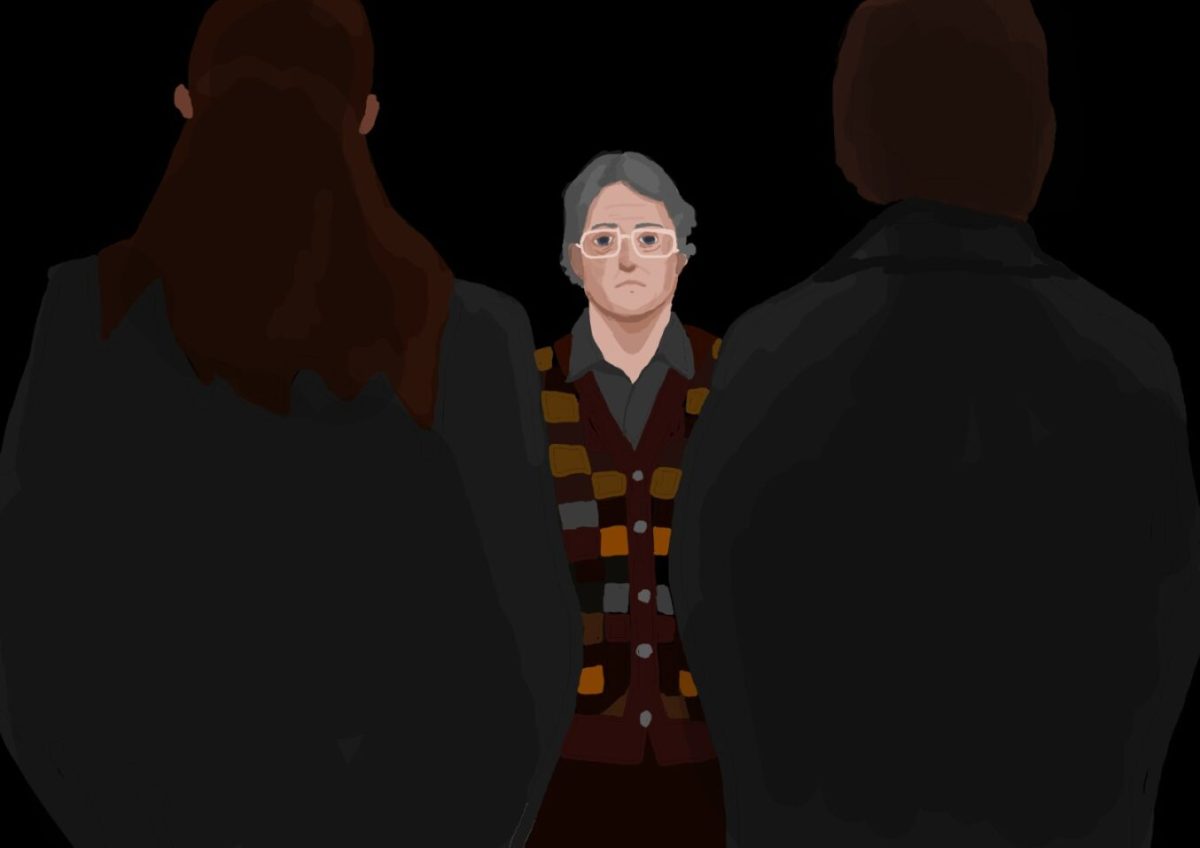

In order to help veterans advance past their demons, Mary Vieten, a board certified clinical psychologist, has an approach tailored to the individual.

Her goal is to “get people to think critically about returning veterans and using a medical format.”

It is a sadly familiar picture that many returning warfighters face when they try to reintegrate into civilian life. Images of disconnected individuals in lonely apartments, chasing down varieties of pills with hard liquor while Veterans Affairs refers them from one office to another. Vieten challenges this conception head on, reminding veterans that having traumatic experiences does not automatically equate to a mental illness. But even when a fighter comes home with all their limbs still attached, their war on the home front often continues.

Prescription drugs, which are written in response to a construct laid out in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, are not enough to cope with past trauma. “It’s OK to take meds and go through psych,” Vieten said. “But you should know the facts.”

Overmedication often results in many problems that exacerbate the issues, resulting in addiction and abuse without any relationships being formed to encourage real healing.

It is for this purpose that the word “disorder” is discouraged. It makes no scientific sense to say that someone entered the war trained, capable and without a mental illness only to leave with a laundry list of diagnosed disabilities.

“They’re all focused on ‘now I am this handicapped person,’” Vieten said. “There’s no validity to that at all. It’s supposed to hurt, it’s called humanity.”

Due to the negative connotation that the word “retreat” has within the military, Vieten calls her gathering an “advance.” It is a program based on compassion and individualized care for veterans who wish to heal by playing into their personal strengths. It tosses aside medication and hospitalization for physical exercise and intrapersonal emotional support. This is done amongst the only people that can truly understand veterans: other veterans.

She recognized that some may classify her treatment as “tough,” even “cruel,” by some standards. However, her resolve for the veterans well-being cannot be denied.

The event also hosted a panel of five veterans from different generations of America’s wars, some sharing with a heavy heart their experiences that still resonate with them today.

Bruce “Doc” Reed, who served as a medevac during Vietnam, recalled firsthand the sacrifices made by the people he was called in to save.

Stories help, but the much more work is needed in order to give veterans the support system they need and deserve.

-By Kilat Fitzgerald