Olivia Volkman-Johnson / Winonan

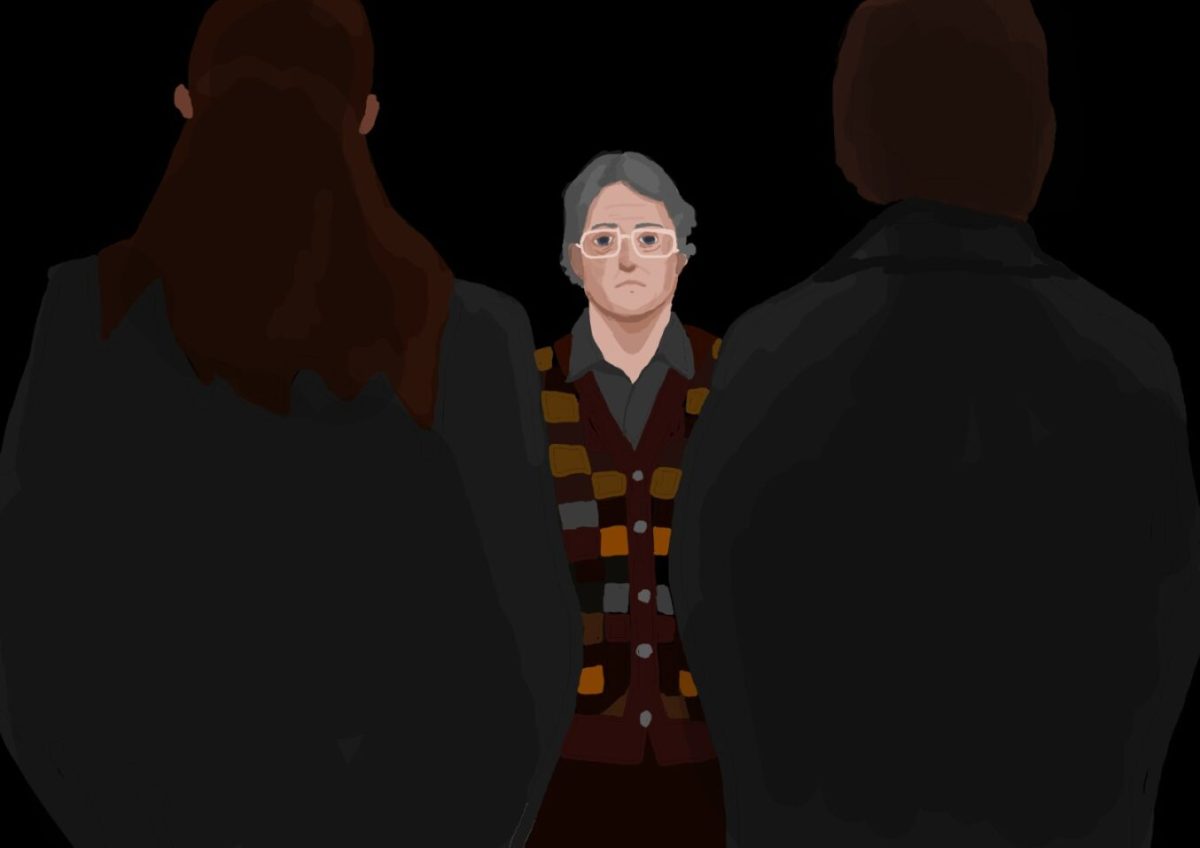

There have been plenty of films about the Civil Rights Movement—such as “Selma” and “Hidden Figures”—which have garnered interest and praise over the past decade. But films do not always accurately depict these events, according former activist Joanne Bland.

Winona State University’s Inclusion and Diversity Office hosted Bland’s lecture, “Hollywood’s Myths and Realities of the Civil Rights Movement,” in Kryzsko Commons last Monday, Jan. 23 in order to address the depiction of the Civil Rights movement in modern films.

“Movies about the Civil Rights movement usually cause controversy whenever they come out, but I think that’s a good thing because it causes you to think about where our nation’s been and how far we’ve come,” Bland said.

Bland, who was born and raised in Selma, Ala., took part in key events during the civil rights movement including Bloody Sunday, the attempted march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala. on March 7, 1965. The march was in protest against the restrictive voting laws that prevented many African Americans from voting.

“When we walked up the [Edmund Pettus] Bridge and… I saw this line of policemen all the way across all four lanes, I knew we were not going to Montgomery,” Bland said.

Bland said this scene in the movie “Selma” was “so realistic that [she] couldn’t watch it.” Though there were other historically factual scenes, Bland expressed displeasure with the movie’s overall accuracy.

“Being from Selma and growing up [during] the Civil Rights movement… you rewrite my history, I try to correct it,” Bland said. “Why would you rewrite my history? I think it’s interesting enough.”

Writers will often alter historical information in order to make films more captivating, Bland added.

“They have to keep your interest for 90 to 120 minutes,” Bland said. “The only problem is people see it and they think it’s the truth.”

Some of the inaccuracies Bland found in “Selma” centered around their portrayal of lead female characters, such as Civil Rights activists Diane Nash and Amelia Boynton.

“In the movie, they were like mumbling idiots. You almost had to replay what they were saying to understand it,” Bland said. “Neither one of those women were like that. They were leaders and [the film] missed an excellent opportunity to show future generations how strong women are.”

Alexander Hines, director of Inclusion and Diversity at Winona State, believes that documentaries do a better job of depicting these events, but many schools are not adequately teaching students about the civil rights movements.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the average state curriculum in the U.S. teaches 19 percent of the recommended content about civil rights.

“When I’m talking to students, they only know the basics,” Hines said. “So they learn about Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, [but] Dr. King was just a figurehead of the movement. We don’t always give the true history.”

Bland said documentaries are generally more factual and urges individuals not to believe everything depicted in films.

“There’s a difference between a documentary and a movie,” Bland said. “Don’t tell me what you saw in a movie; tell me what you’ve researched. If you had said documentary, I might’ve given you [the] time.”

Bland said learning accurate information about the Civil Rights movement is necessary for students and adults in order to understand the origin of prejudice in the U.S.

“When this history is written right, we have a clear understanding of people. And I truly believe racism is 99.9 percent fear,” Bland said. “Once we get to know each other, that fear is erased.”

Despite the hesitance and discomfort that individuals may feel, Hines and Bland said education and conversation are essential to eliminating racism in the U.S.

“If people were more aware and more educated from an inclusive curriculum, maybe we would have more critical thinking around the things that happened in America instead of repeating history’s mistakes,” Hines said.

“I truly believe that movements for social change are like jigsaw puzzles,” Bland agreed. “Everybody has a piece. And if your piece is missing, is the picture complete?”

By Olivia Volkman-Johnson