Courtney Kowalke/Winonan

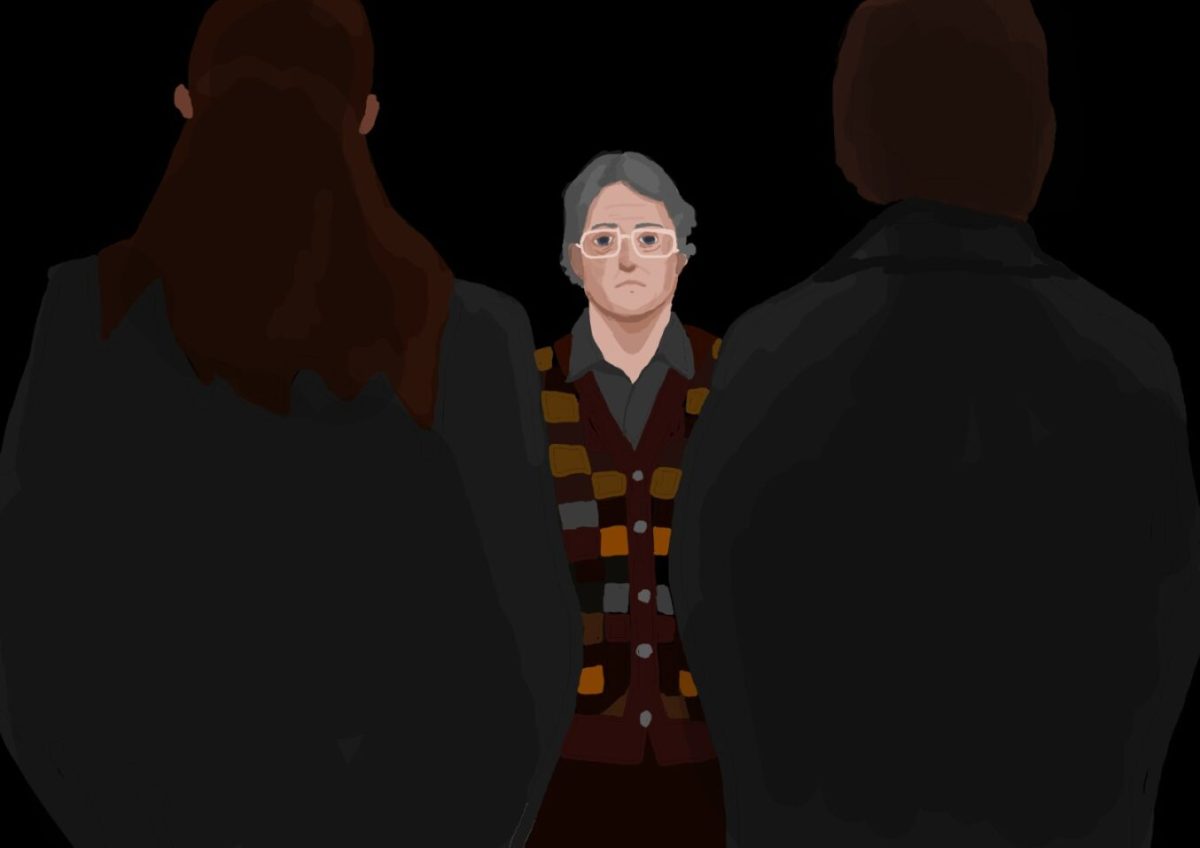

Winona State University’s weekly CLASP Series presented “How I Wish To Be Remembered: The Use of an Advance Medical Directive – It’s Not Just For Elderly” to inform students about living wills and how to prepare for the unexpected.

Held Tuesday evening in room 155 of Gildemeister Hall, director of Student Conduct and Citizenship Alex Kromminga addressed the audience regarding “the realities of tough medical decisions made when young people are the victims of death by accidental injuries.”

“I promote having an advance medical directive, but I don’t currently have one myself,” said Kromminga, who also holds an Executive Juris Doctor (EJD) and teaches Masters courses at Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota. “I trust my wife and my family to make the right decisions for me if I’m ever in need of dire medical care, but now I’m realizing, yes, I should probably really have one just in case.”

Fortunately Kromminga “found some good tools” for drafting an advance medical directive during his researching.

As explained by Kromminga, “An advance medical directive is a way for an adult to tell family, friends and medical providers the kind of treatments the victim would want in case of emergency and who will speak for them in case they’re unable to speak for themselves.”

Also known as living wills, personal directives, or advance decisions, these directives outline actions the patient would prefer would be taken if he or she were no longer able to make decisions due to illness or incapacity.

The instructions appoint someone—usually an agent, health care proxy, or durable power of attorney—to make such decisions on the advance directive writer’s behalf.

“With the growing ability of medical technology to prolong life, it is important to have plans like these in place,” Kromminga said.

Kromminga cited the famous legal struggles of Terri Schiavo to illustrate another important reason advance medical directives are important. “These documents can help avoid family feuding since your wishes are made explicit. You still have the power to decide what happens.”

Often thought of in relation to older adults, advance medical directives are also important for teens and young adults.

According to Kromminga’s research, every year more than 25,000 people between the ages of 15-34 die of accidental injuries, and very few victims have established advance medical directives.

“If you’re a young person going into or in college, you’re going to be away from home, maybe for the first time and maybe a lot,” Kromminga said. “You will travel a lot. You might travel the world. It’s important to have a copy to make sure your wishes are known wherever you go and to be prepared for anything.”

Kromminga also noted an advance medical directive can be revoked or changed at any time, a feature young people will most likely require.

“Now you’re single and young,” Kromminga said. “As you grow up, you’re gonna want to change what’s stipulated in your directive.”

Advance medical directives only being necessary for the elderly was one of 10 myths Kromminga examined with students.

As explained by Juris Doctor Charles Sabatino, “The stakes are actually higher for younger persons in that, if tragedy strikes, they might be kept alive for decades in a condition they would not want. An Advance Directive is an important legal planning tool for all adults.”

Kromminga highlighted several forms readily available online for those looking to draft something general.

The organization Aging with Dignity’s Five Wishes outline “makes you ask the questions you should ask,” Kromminga said.

According to the organization’s website, “Five Wishes has become America’s most popular living will because it is written in everyday language and helps start and structure important conversations about care in times of serious illness.” The Five Wishes document is recognized as a legally binding advance medical directive in 42 states including Minnesota.

Conversely, the I Decide organization is aimed at younger people drafting advance medical directives. Kromminga likes “the idea that it can accessed from anywhere” via the organization’s website so the directive is available for local hospitals when the person is traveling.

Kromminga had the audience assess a directive he drafted after viewing several resources. “It’s an open-ended example that stipulates some time points but is open to possibility,” he said. “It’s flexible, short and sweet.”

When writing an advance medical directive, Kromminga learned to question his motives. Using prompts like “My life is only worth living if I can…” and “If I am dying it is important for me to be…” Kromminga asked to students to think about what matters now that will remain relevant if they become terminally ill or injured.

He also asked students to consider how they want to be remembered when writing an advance medical directive.

“Sometimes we forget there are going to be living people around after this,” Kromminga said.

Contact Courtney at [email protected]