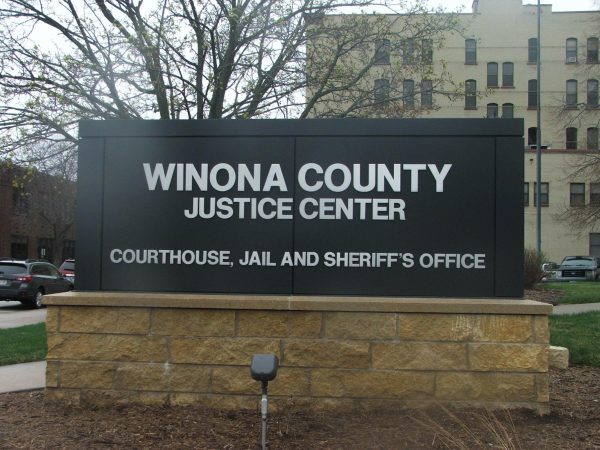

Local activist group concerned over Sheriff Office’s new drones

Winona County Sheriff’s department recently acquired it’s fifth drone, having infrared heat seeking (FLIR) capabilities.Community Not Cages stressed their concern over the use of FLIR drones, claiming they can look through structures to read individual heat signature.

February 24, 2021

Community Not Cages, a local activist group, voiced their concerns to Student Senate on Feb. 16 over Winona County Sheriff Office’s acquisition of five drones.

Tova Strange is a second-year student at Winona State University majoring in psychology and minoring in criminal justice and communications, who is also involved with the local activist group Community Not Cages.

Community Not Cages was created over a previous Winona County decision to create a new jail, Strange said.

Strange said Community Not Cage’s main concern over Winona County’s new drones is the potential for privacy rights to be impeded upon.

Legal language surrounding drone use was especially an issue of concern for Strange, who said, “anything they [police] have can be used for us or against us. I’m not opposed to using drones for finding missing people, but I oppose the ambiguous laws.”

The Chief Deputy for Winona County’s Sheriff Department, Jeff Mueller, said drone technology has been available for use by Winona County since 2018.

Mueller said Winona County had policy and usage for drones dating back to 2018, where their initial search operation and rescue drone was funded by outside donations that varied between 50 and 500 dollars.

Mueller said the new acquisition resulted from a recent insurance claim, which sought to replace a forward-looking infrared heat seeking (FLIR) drone that was lost on a previous case.

With leftover money from the claim, Winona County then purchased three more drones, each with different capabilities.

Of the drones that were purchased with the leftover insurance money, one is a non-aerial device used for underwater search and rescue, while the other two are standard aerial devices, one equipped with a spotlight and another with a loud speaker, according to Mueller.

As for Winona County’s fifth drone, Mueller said it was given to the department by the Southeast Minnesota Violent Crimes Task Force, who seized the “cheap” device from a previous narcotics case.

The primary use of the drones are for search and rescue operations, such as missing person cases, Mueller said.

Strange however questioned the department’s reasoning, arguing that there is only one active missing persons case in Winona listed on the Minnesota Department of Public Safety’s missing and unidentified persons clearinghouse website.

Mueller said he views the drones as, “more tools in our tool belt to help find the people,” when a case emerges.

All drone usage is subject to a Freedom of Information Act request but may depend on “ongoing criminal cases,” or other legal matters, Mueller said.

Community Not Cages also stressed their concern over the use of FLIR drones, claiming they can look through structures to read individual heat signatures.

Mueller, however, said FLIR drones don’t have those types of capabilities.

“[FLIR drone] doesn’t see through walls. It can see through dense brush. [FLIR drone] would not be used to locate someone within a structure because it wouldn’t work. If there’s heavy tree canopy, or a heavily wooded area, it still struggles to find a heat signature,” Mueller said.

FLIR drones also cannot be used without a warrant, Mueller said.

The remaining four drones can be used without a warrant however, something Community Not Cages has expressed concern over.

Strange used the example of Golden Valley’s police department actions last summer, where police used drones to gather surveillance on nudity at a Minnesota beach, to express Community Not Cage’s concern over drone usage.

The controversy regarding the further advancement and use of surveillance technology exposes a gray area in the legal system.

Matthew Bosworth teaches Constitutional Law at Winona State.

Bosworth said most legal language surrounding drone usage has been deferred to state and local governments, due to a lack of action on the federal level.

The last Supreme Court case regarding surveillance technology goes back to 2001 in the case Kyllo V. U.S, Bosworth said.

This case dealt with heat seeking technology and whether or not the evidence gathered from the technology was admissible in court.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of Kyllo, arguing under the Constitution’s fourth amendment that the obtaining of evidence fell under unlawful search and seizures, Bosworth said.

Bosworth, however, mentioned another case: Dow Chemical V. U.S 1986. In that case, the courts ruled in favor of high imagery government surveillance photos because it fell under plain view, a rule established under the fourth amendment that allows for the seizure of evidence that is within law enforcement’s sight.

This creates a complicated situation when trying to distinguish which category drones fall under, Bosworth said.

While federal legal language surrounding drones may be scarce and outdated, Minnesota state statutes have been up to date with the current technology.

Bosworth said while the policy had largely ambiguous language, it likely could be in effort by the legislature to cover a wide range of potential scenarios.

Bosworth said the state statutes have both a “pro-civil liberties” aspect and one “in the other direction.”

The state statute allows for general collection from the public area over reasonable suspicion, a language choice that Bosworth says restricts law enforcement’s usage of drones.

Bosworth said he believes the language surrounding public disclosure however may “err on the side of secrecy,” adding that, “to say that law enforcement should “consider” notifying the public is a recipe for non-disclosure.”

While it isn’t illegal to withhold drone information, Bosworth said, it was a bit concerning due to possible civil liberties violations.

Bosworth hopes decisions surrounding drones are decided by the legislatures and not the courts in coming years.

Regarding student awareness of surveillance use by law enforcement agencies, or private companies, Bosworth said, “students should be aware that this might be an issue. I don’t think I’d spend a whole amount of time worrying about it.”

Strange hopes students will attend Winona County’s next board meeting on March 9 at 9 a.m., where the Sheriff’s Office will be available for public comment.