Documentary ignites race discussion

Despite a seating shortage students continued to file into the SLC Auditorium Wednesday for the screening of “I Am Not Your Negro”.

October 4, 2017

As the lights dimmed in room 120 of the Science Laboratory Center on Wednesday, Sept. 29, latecomers looking to find a seat for the screening of Raoul Peck’s documentary “I Am Not Your Negro” instead found themselves having to find a spot on the already crowded stairwells.

Students, professors and community members filled every seat—and then some—for the second event in Winona State University’s annual Consortium for Liberal Arts and Science Promotion (CLASP) lecture series.

Since 2004, CLASP has featured talks by professors concerning scholarly research and other topics of interest.

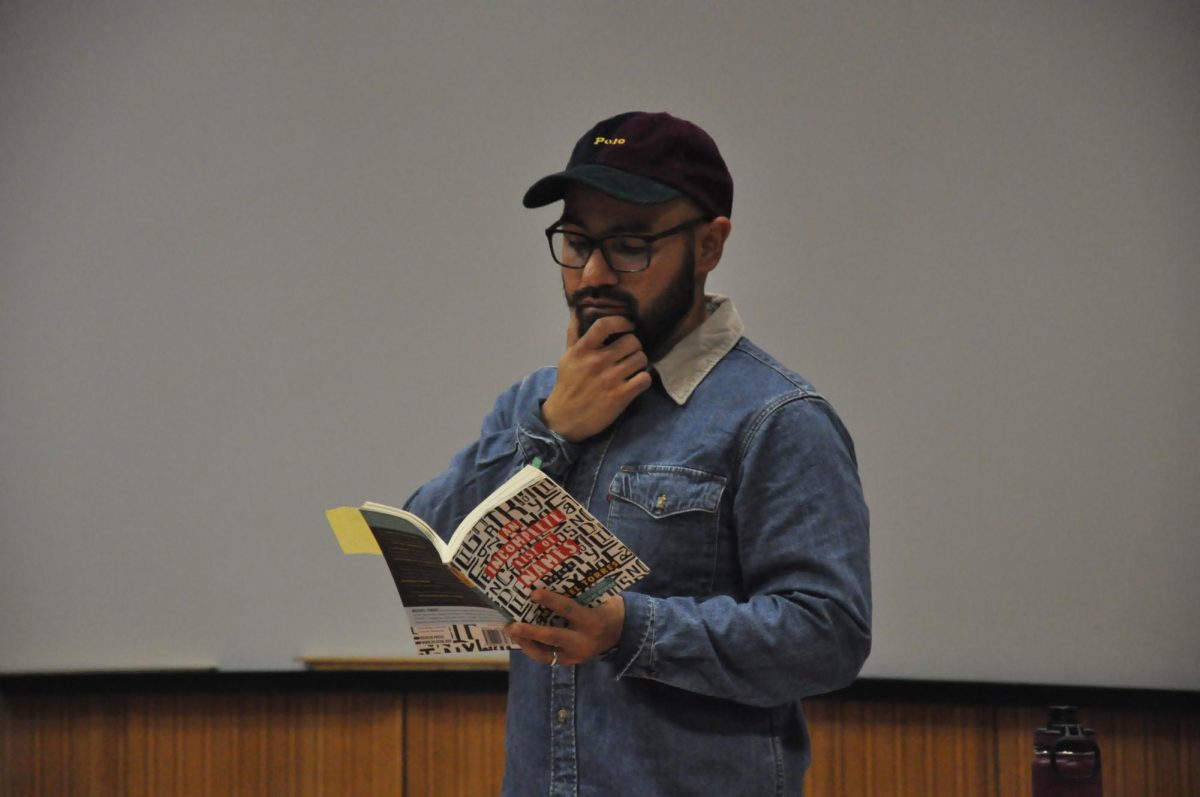

Last Wednesday’s event featured J. Paul Johnson, a professor of English and film studies, who introduced the documentary by giving a brief overview of the life of James Baldwin, whose written works provided the basis for the film.

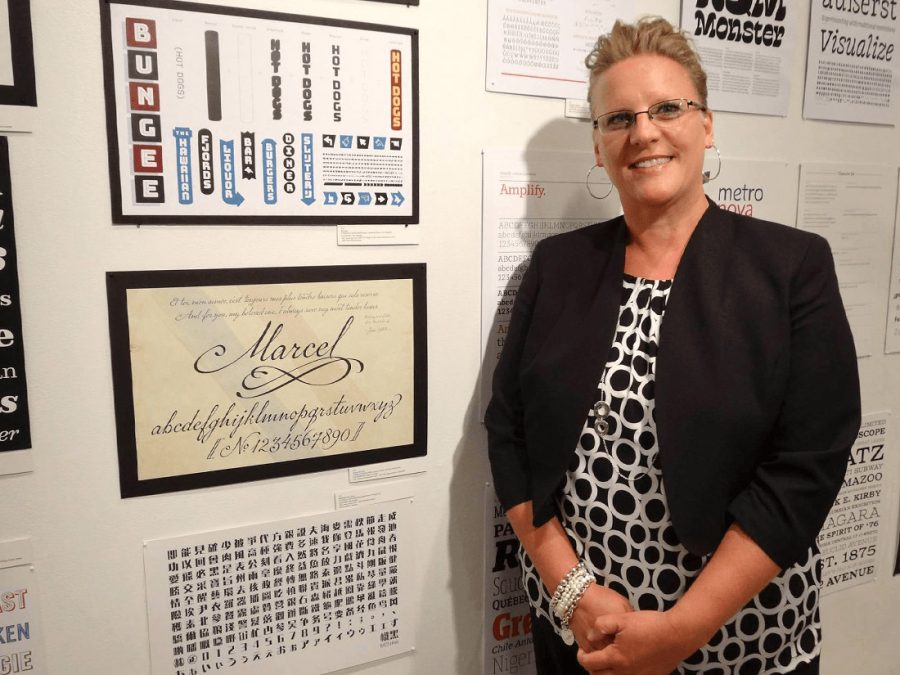

A discussion panel with English professor Gretchen Michlitsch, political science and public administration professor Fredrick Lee and new ethnic studies professor Cassandra Dame-Griff followed the screening.

“The initial conversations about this particular documentary began in my home department, the English Department, in early last spring [when] the film was first released,” Johnson said. “James Baldwin is one of America’s literary and intellectual giants. For there to be a major feature length documentary about him is news.”

Baldwin was an author renowned for both his fictional and non-fictional work, as well as a civil rights activist. He personally knew Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers, all of whom were assassinated in the 1960s.

Upon his death from stomach cancer, Baldwin left behind an unfinished 30-page manuscript concerning the lives and deaths of those three men.

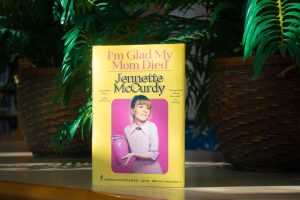

“I Am Not Your Negro” director Raoul Peck

sought to complete Baldwin’s project by combining footage of African-Americans throughout history with Baldwin’s writings. Actor Samuel L. Jackson provided narration for the film.

Johnson said he was interested in bringing the film to campus in the spring, but it was not available at that time. Over the summer, he tracked down the licensing rights and then worked with the Frozen River Film Festival and his colleagues in ethnic studies to make the screening a reality.

From left to right, Professors Gretchen Michlitsch of the English department, Fred Lee from political science, and Cassie Dame-Griff from ethnic studies all formed a discussion panel following the film screening.

“Here’s a film in particular that I really hope should open itself up to a rich discussion from a number of perspectives,” Johnson said.

To promote this dialogue, Johnson invited Michlitsch, Lee and Dame-Griff to form a discussion panel based on three distinct perspectives.

“Gretchen Michlitsch from the English department is an expert of African American literature and can look at and talk about Baldwin’s contribution to American literature,” Johnson said. “Cassie Dame-Griff is a new hire in ethnic studies who I believe can speak to the film’s identity politics and Fred Lee, who is a professor in political science, can represent the political spectrum by speaking to the strife and protests that accompanied the civil rights movement that Baldwin himself was hoping to chart in the 1960s.”

The professors on the discussion panel shared their first impressions of the film before opening to the audience’s questions. Michlitsch said she saw the film as a starting point for discussing issues on race.

“We’re in Minnesota where it’s very white and relatively segregated and Baldwin mentions in this film that the apathy and ignorance are a result of segregation,” Michlitsch said. “And so, I see tonight in this film some of the action taking place on campus as one way of decreasing that ignorance on our part as a city, as a community, as a campus.”

Fifth-year student Andrea Boe, a public relations major and film minor, made a similar comment after the event.

“As a white person, it is so easy for me to climb into a little bubble and not have to acknowledge that these things are happening and it’s my responsibility to take myself out of it and to learn more,” Boe said.

Within the discussion, Lee responded to one audience member who said she thought that by being white, she herself was inherently prejudiced.

“Doesn’t the word prejudice come from this notion of prejudging,” Lee said. “I don’t know of anyone on Earth who is not prejudiced. The question is ‘What do we do with our prejudices?’ We can act upon them, we can try to minimize them, [or] we can recognize them.”

A major discussion point of the film was whether significant positive change has truly occurred in regard to modern race relations. In multiple scenes, Baldwin’s words from the civil rights movement were overlaid on modern-day footage, leading viewers to connect the two, despite the gap between eras.

Fifth-year student Jake Nielsen, a creative digital media and film studies double major, said that this idea of progress was his biggest takeaway from the film.

“We’re still fighting the same battle that we have been since the Civil Rights Movement back in the ‘50s and ‘60s,” Nielsen said. “[It’s] important to have historical context for what we’re still fighting for, so we can recognize it in today’s day and age.”

One audience member made a similar comment within the discussion and asked Lee how society can say that it has progressed if there have only been a couple of improvements.

Students, professors, and community members filled the seats as well as the nearby floor space for the documentary film “I Am Not Your Negro” screening on Wednesday, Sept. 27th in SLC 120 in Stark Hall. A discussion panel followed the screening.

“I’ve been around long enough to know I was first a ‘negro,’ now I’m a ‘person of color,’” Lee said. “The very language that we use to describe people of color has changed over time. Is that a measure of progress? I don’t know. I’m not sure that I would take completely to heart your point about progress because as I said, I’ve lived through it, so you’d have a hard time convincing me that we haven’t made progress. Just intellectually I can’t accept it and I know experientially I can’t accept it. But I would agree that we can’t rest on our laurels.”

Dame-Griff said that our society has had two kinds of segregation in our history: de jure and de facto. De jure refers to the legalized segregation that Lee experienced while growing up. De facto refers to the non-legalized segregation that Dame-Griff said is still in place today.

“I think about how much progress we’ve made but also how much we’re told we’ve made and I think about how my high school was split down the middle,” Dame-Griff said. “It was split between the Latino kids and the white kids. When they re-zoned us, all of the Latino kids and the working class kids ended up at one school and the white and middle class and wealthy kids ended up at another.”

Lee said that he does not think the issue of race will ever go away.

“Maybe the bottom line for me is this, I think as long as I can see a difference in your skin color and mine, and you can see a difference, the issue that we deal with about race will always be present,” Lee said. “That’s what I believe. That doesn’t make me pessimistic but I like to think it makes me realistic because I know I’m not colorblind. The reality of it is that when we see people, the first thing we see is color. Now how do you get beyond that? I think most of us can if we make the effort.”

While the discussion went several directions, including a dialogue on race and identity, one audience member asked how change can occur at Winona State.

“I think it happens in a lot of ways,” Dame-Griff responded. “It happens around student interest [and] student adjudication. It also happens around talking to your faculty, saying, ‘What’s missing?’ The better you get to know your institution, the more chance you have to make change.”

As the evening drew to a close, Johnson expressed his hope for the discussion to continue.

“While we may be out of time for the moment and temporarily suspending the conversation, this is one that I hope goes on for a very long time,” Johnson said.

His words echoed an earlier comment by Lee.

“Keep asking that question that you are raising,” Lee said. “Just keep asking that, and I’m not sure that every question can be answered to your satisfaction, but you deserve some answers. And I think that if you keep asking questions, eventually there will be some response.”