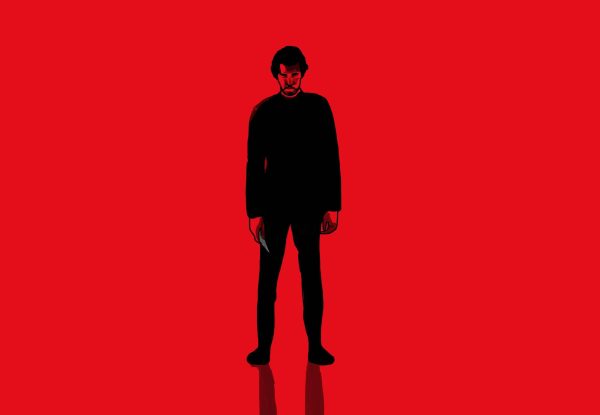

Film in review: “On Body and Soul”

February 7, 2018

In a world so heavily connected by the internet, it’s very easy to entrap yourself in your own bubble. With so much information instantly at our fingertips, we are allowed two paths: liberation from our own prejudices via seeking the truth, or further decay into ignorance and misunderstanding via seeking those who share in your misconstructions. One such smaller scale example is evident within the film industry. The majority of countries across our shared globe have their own film industries. Movies are made, distributed and witnessed by eager audiences everywhere. In the United States, we are often only exposed to films concocted through the Hollywood and sometimes independent American systems. This means a world, LITERALLY A WORLD, of fantastic storytelling is falling into oblivion separate from America’s consciousness. Unlike novels and music, film is a visual medium of which can be expressed universally across our planet in methods not much different than those standardly used in Hollywood (if you don’t mind reading subtitles on occasion of course).

The film’s industry’s increasingly vital reliance on streaming has been successful in popping many self-contained bubbles, but certainly not all. So, this week I decided to run with an unconventional pick. After announcing it as one of the films in contention for “Best Foreign Language Film” this year at the Oscars, Netflix has now unveiled it on its platform in a very subdued fashion, yet again another reflection of the general public’s unawareness of world cinema’s significance.

Perhaps the most freeing aspect of watching a foreign film is the language barrier. It may sound bizarre because the word “subtitles” is prone to making a large majority of people vomit, but allow me to explain. With the utilization of a language and speaking style altogether different than our own, we are ridded of the inconvenience of “bad acting.” No longer are we able to see through the façade of scripted scenes and forced dialogue. The world just feels real. Consequently, new languages often shepherd in new faces who understand the language to portray our characters. We’ve seen similar performances a million times so our brains are prone to seeing fiction rather than reality, but unknown faces and a non-comprehendible language strangely can establish a world that feels more real than staged.

“On Body and Soul” strives in all areas including, characters, dialogue and performances.

The film focuses on a man named Endre, played by Géza Morcsányi, who is the director of a slaughterhouse with a disabled left arm and often contained personality. Endre meets a woman, Mária, played by Alexandra Borbély, who works underneath him as a quality inspector of the meat and exhibits incredible precision as well as autistic tendencies. Both are very different people who seem to exhibit an unexplained attraction to each other.

As the film progresses they discover that they share the same dream world every night when they’re sleeping, and as a result attempt to traverse their differences to grow closer together. The film, although small and self-contained, unlike the big and bombastic dream-based flick, “Inception,” is equally stunning. The deplorable environments of the real-world slaughterhouse greatly differ from the way in which the still and breathlessly beautiful dream world is captured onto the screen. Overall, “On Body and Soul” is a breathtaking attempt to showcase the wonderful impact dreams can have on us, both as real life aspirations and mid-sleep journeys that transport us into a land.

Consensus: If in the mood for a film that is an absolutely unique but undeniably touching experience about the two very complicated topics of dreams and human connection, then “On Body and Soul” is the film for you (if in possession of an open mind as well as curiosity for the world around you, of course). 4/5

Robert T. Wisnyovsky • Oct 1, 2022 at 2:39 pm

Hi,

You might have a typo as the male lead actor’s name spelled incorrectly, not Géza Morcasányi but Géza Morcsányi.

Kind regards.