The Sholom Home’s downfall to vacancy

October 21, 2020

Every year, two million food enthusiasts visit the Minnesota State Fair, based in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, unaware of a quiet, ravaged, dystopian structure only a block away.

The building rests directly across the Fair’s main entrance on Snelling Avenue, giving commuters a haunting look of what can happen to neglected properties. Although the building resides on one of the busiest roads in the Twin Cities, it is possible that very few know of its troubled legacy.

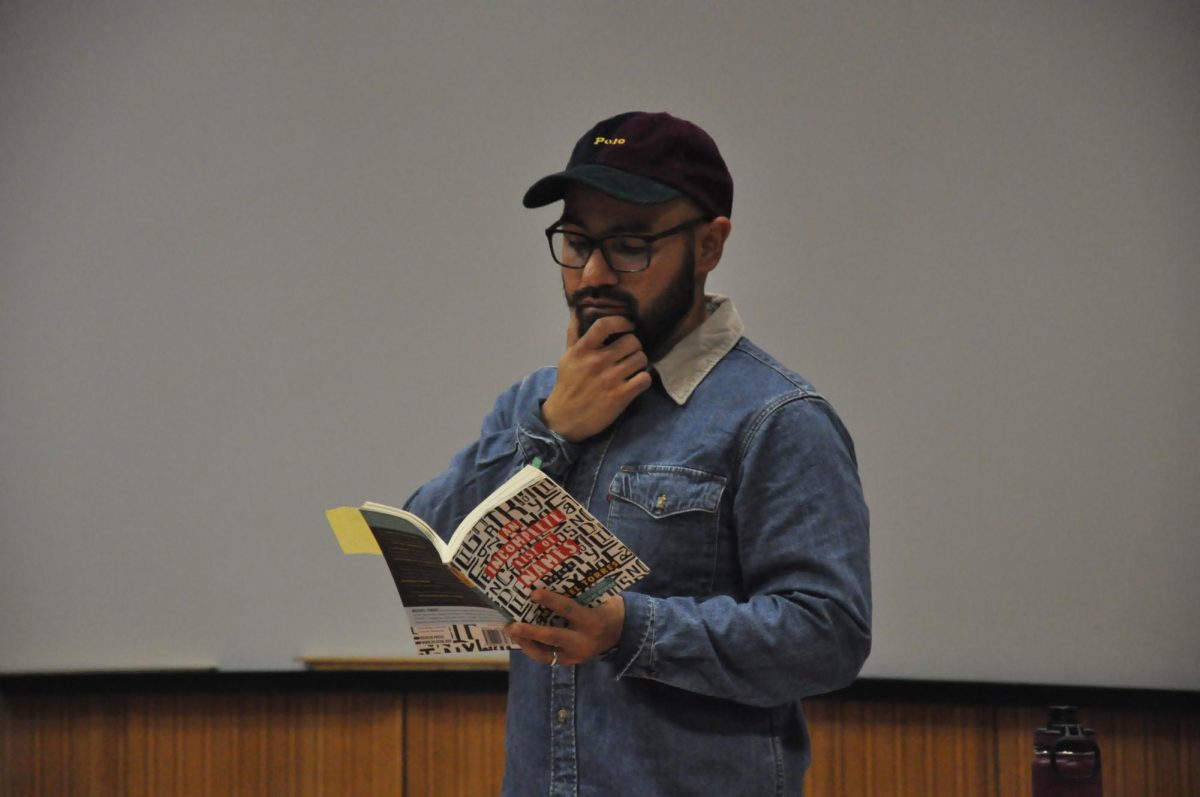

For former community council member David Arbeit, the Sholom Home’s legacy would prove to be a lasting heartbreak.

Arbeit assumed his duties as board chair in 2008, unaware that a social bomb was ticking away in his own back yard.

The Sholom Home had recently closed one of its properties in Falcon Heights, which had been in operation since the 1920’s. With its closure, murmurs began to circulate around the neighborhood regarding the site’s future use, Arbeit said.

Now 76 years old, Arbeit still holds a distaste for what unfolded in his neighborhood, District 10, in 2008.

District 10, a sub area of Minnesota’s fourth district, is known to be an inclusive neighborhood, a neighborhood with institutions such as assisted living centers, nursing homes and Hubert H. Humphrey Public Works center – named after a former Minnesota senator – a place that has garnered support from the neighborhood, Arbeit said.

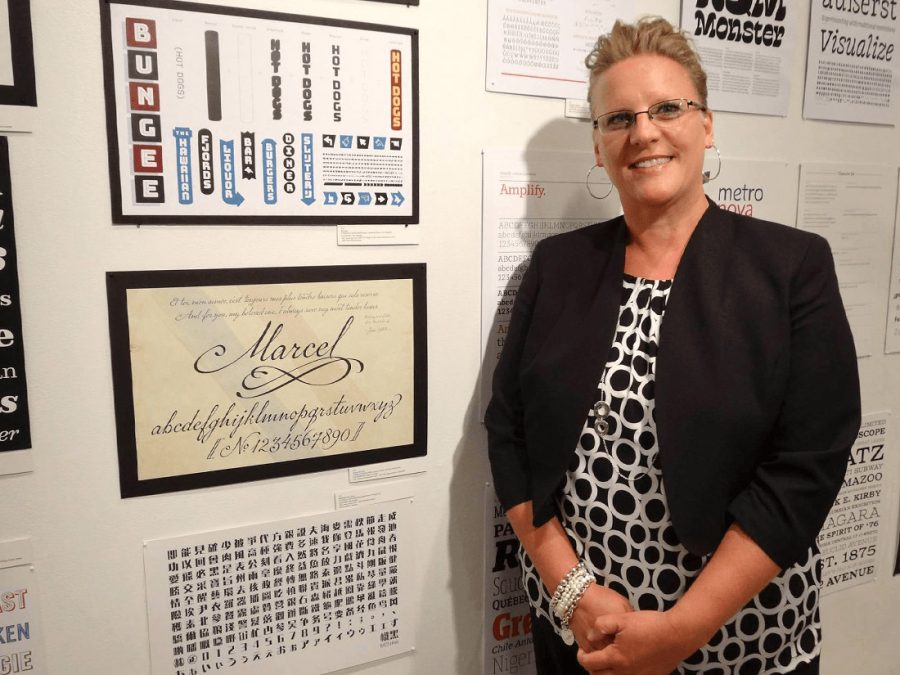

Rhonda DeBough was the community organizer who served with Arbeit. DeBough remembers the Sholom Home’s closure and how the community was eager to put something in its place.

Like Arbeit, though, DeBough is still troubled by what transpired there.

Why do two former community council members feel jaded by their District and what does it have to do with the former Sholom Home building? To find these answers, the fear within the neighborhood needs to be addressed.

Fear is corrosive. It strips away our logical processing center and instills a fight-or-flight response because the mind believes its survival is being threatened. Fear may force some to make decisions that compromise their morals. It can divide and change a community, no matter the amount of education its citizens possess. When trying to explain District 10’s atmosphere in 2008, fear manifests as the culprit.

Since its closure, the Sholom Home has experienced a lightning decline, with the exterior of the building suffering first. Without proper maintenance, the building’s grounds went from hospitable and welcoming to hostile and cold.

Weeds penetrate the vacant concrete parking spots, celebrating their victory over human interference. Common gathering areas look eerily similar to that of an abandoned town whose population up and left. The internal integrity of the building is decomposing due to broken windows, vandal graffiti and failed construction projects. What was once a functioning nursing home with state-of-the-art technology had now become a Hobbesian state of nature, sheltering the occasional weary traveler.

The Sholom Home property had become what District 10 residents feared: a location of criminal activity that could diminish the value of the neighborhood.

In 2008, however, the newly vacant Sholom Home was still a beacon of promise.

RS Eden, a local nonprofit, recognized the utility of the building and began to probe the possibility of acquiring the freshly abandoned building. Behind the scenes however, more sinister forces were at play.

RS Eden was established in 1971. They are classified as a community health organization, an area that has largely been referenced in recent days following the deaths of mentally ill citizens by the hands of law enforcement. In short, they help people with substance abuse problems and correctional issues by rehabilitation in an effort to bring them back to society. A nonprofit that, as Arbeit said, has a good reputation and gets support from the St. Paul Foundation, an organization that give grants to nonprofits and helps identify community problems.

But RS Eden is “the sort of service provider folks here support but would rather have it somewhere else,” Arbeit bluntly said.

RS Eden’s first proposal lacked unanimous approval.

DeBough remembers a vocal minority that resented the possibility of a treatment facility located in their backyard. DeBough recalls neighbors being insistent on knowing whether or not sex offenders would be housed at the facility. RS Eden could not confirm that there would not be, due to the fact that they are a rehabilitation center. DeBough pointed out that the sex offender “hot topic” was not proportional to the services RS Eden provides. Most of what RS Eden focuses on is drug rehabilitation, which can include sex offenders but also may not. DeBough mentions Dan Cain, former CEO of RS Eden, trying to quell fears by explaining that sex offenders are not an issue at any other facility they operate. It did not work.

With RS Eden’s exploration of the former Sholom Home known to the community, a manufactured misinformation campaign then began to take shape.

DeBough remembers attending a meeting at a park located not far from the former Sholom Home. 10 to 15 neighbors were gathered, speaking in hushed tones as DeBough drew near.

“That’s Rhonda, don’t talk,” said the suspecting neighbors as DeBough closed in.

What had been transpiring was a secret meeting designed to drive out RS Eden. Twenty-dollar bills were collected from each attending member, minus DeBough, to craft an anti-RS Eden flyer. The result was shameful.

At some time, whether overnight or during the day, flyers appeared in neighbors’ doors depicting a park bench with drug needles and alcohol bottles. Along the grim imagery was a message, false in nature but effective in practice, that asked if residents wanted their neighborhood to be depicted as illustrated and claimed it would if RS Eden bought the Sholom Home.

The sole individual who created the flyers was never identified.

Neighbors contacted DeBough expressing their concerns. DeBough urgently contacted Arbeit, laying down the ominous news.

Something had to be done.Another community council meeting was organized, one which Arbeit says was the biggest he has ever witnessed. 300 to 400 people gathered for the community council meeting, with loud dissenters protesting RS Eden’s proposal. Acknowledging the neighbors’ concerns, RS Eden decided to rescind its plans to purchase the former Sholom Home shortly after.

The experience had lasting ramifications on District 10’s neighborhood – some that manifested in the form of elections. Some associated with the misinformation campaign were voted onto the council, DeBough said.

Leah Retamozo was appointed as the board chair after Arbeit, and Arbeit remembers the nastiness that surrounded the community council.

Retamozo had moved into the neighborhood near the former Sholom Home in 2007 and wanted to contribute to the community. Retamozo had become friends with DeBough, who encouraged her to run for board chair during the 2010 elections.

Once appointed however, Retamozo’s optimism quickly diminished. Retamozo and DeBough recall the disrespect they endured from some of the council members, some that participated in the disinformation flyer campaign. Retamozo resigned from her position very early on due to the ugliness of the experience, calling the ordeal “extraordinarily negative.” DeBough was notified that her position was posted and that she was welcome to apply, signaling an end of her time with District 10.

Residents were deeply affected by the malicious flyer campaign. It was not that Arbeit and DeBough were not okay with residents rejecting RS Eden – it was the malicious misinformation campaign that was used to convey the point that struck a chord.

Arbeit concluded that the event was a preview of the times we currently live in, which is full of misinformation and flat out lies meant to achieve specific ends.

DeBough, on the other hand, put partial blame on the system that is community governing.

Looking back, DeBough stresses that she would have tried to handle the ordeal in a more civilized fashion, tackling fears head on as a whole, not divided. DeBough suggested a resolution system designed to repair communities after traumatic, or polarizing, events. DeBough has not been to a community council meeting since.

The Sholom Home still sits vacant. Multiple plans to redevelop the former nursing home have fallen short throughout the years, with the most recent acquisition still in the planning phase.

The eye sore has become an open wound for District 10, leaving neighbors with a less than satisfactory conclusion to a grotesque campaign. Criminal activity seems to swell at the former Sholom Home. What District 10’s anonymous flyers warned of became reality due the inability to utilize the former nursing home – not because of RS Eden.